Published on May 13, 2022

The last few weeks have been dominated by the elections. As I watch the various advertising campaigns and listen to the debates between politicians, I can’t help but wonder what our students might be learning about civil dialogue. In particular, through the media and watching our politicians in action, are they learning the importance of having well-reasoned arguments based on evidence rather than assumption?

Last year I had the privilege of listening to the Young Aurora Award presentations. Once the presentations were completed, there was a panel discussion centring on the question of how to ensure humanitarianism was a driving force in education for everyone. My takeaway was that if we want education to be a force for change and peace to permeate every corner of our lives, then we have to focus on challenging our assumptions and reflect on the stories we tell ourselves. This is so critical at a time when the media, and our social media feeds, communicate polarising and emotive opinions.

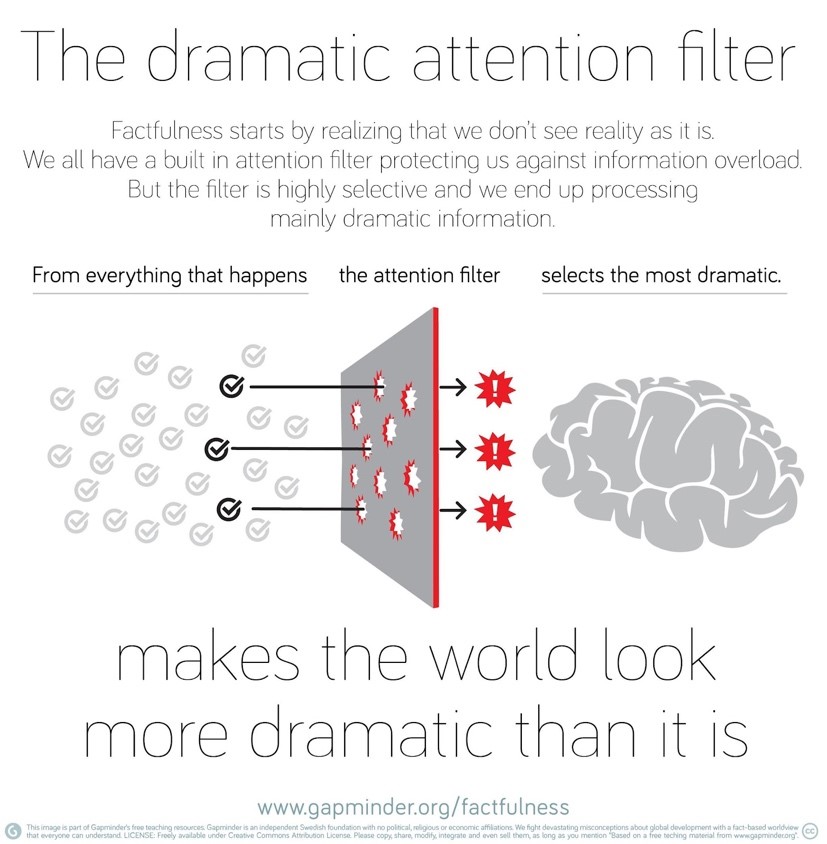

To ensure we pursue a humanitarian agenda in schools, we need to slow our thinking and check our assumptions at every turn. At this juncture it is useful to keep in mind the concept of “factfulness” (see Hans Rosling’s book, Factfulness: Ten Reasons We’re Wrong About the World and Why Things Are Better Than You Think and the Gapfinder Project). According to Rosling we are hard-wired to be dramatic or make cognitive leaps in logic based on the worst-case scenario rather than the facts that are before us. As a result our perceptions are often skewed:

This is an interesting concept for us in schools not only in terms of the work in the classroom (how do we ensure students develop as critical thinkers who are skilled at drawing conclusions from evidence not just their own biases) but also in relation to the assumptions that often guide our thinking everyday.

Looking at our instincts

Most recently I have reflected on this in student discussions about grades. When it comes to assessments, student (and parents) often become locked in the “single perspective instinct”. This is when we see only one solution to an issue. In the case of assessment grades, this can be the intense focus on the grades themselves as the determining factor for success, which makes it hard to be flexible when the grades are not as expected. Underlying grade conversations are also generalisations about what success looks like – high grades at the expense of other ways of measuring competence and mastery. Being a slave to our “dramatic instincts” and not pausing long enough to ask the right questions (see “rules of thumb” in the below graphic), takes us away from evidence-based conclusions and factfulness as a concept. This is a natural human tendency that we need to monitor in ourselves and our students.

Creating a sense of optimism

Alongside factfulness, we also need to tell stories that cultivate a sense of optimism and hope about humanity, most especially as we witness our politicians battle it out and war rage in the Ukraine. Rutger Bregman in Humankind: A Hopeful History aims to do just this. Bregman encourages us to think critically, step back from the sensationalist news stories and social media feeds that dominate our lives, and instead remember that “people are deeply inclined to be good to one another” (p. 397). I wonder, most especially as politicians dominant our newsfeeds, are we telling hopeful stories? And as adults are we helping young people slow their thinking so they actively listen to those that think differently to themselves? To understand why people turn to ideas that are different to our own, we need to take time to listen and understand, and we need to take the time to read and engage with well-researched and informed texts. This quote from Bregman’s books reminds us to consider which ‘wolf” we are feeding through the stories we consume:

“An old man says to his grandson: ‘There’s a fight going on inside me. It’s a terrible fight between two wolves. One is evil–angry, greedy, jealous, arrogant, and cowardly. The other is good–peaceful, loving, modest, generous, honest, and trustworthy. These two wolves are also fighting within you, and inside every other person too.’ After a moment, the boy asks, ‘Which wolf will win?’ The old man smiles. ‘The one you feed.’ (p. 3)”

As we watch our politicians “debate it out” and disparage each other, questioning our assumptions and nourishing ourselves on the stories that have the most positive impact on our own lives and those of others, builds hope. This is what our students and children need from us so they can tap into their capacity to be change makers who can foster peace in their communities.

Works Cited

Bregman, R. Humankind: A Hopeful History. Bloomsbury: UK, 2020.