Published on December 1, 2022

The end of the academic year is a time of change for everyone. Students are transitioning to new year levels or school sections, staff are saying goodbye to classes and preparing for new groups of students, and some staff and students are leaving the school for new horizons.

This week I was speaking to a group of staff about change and transition and the way in which we can reframe our thinking about change and simultaneously allow ourselves to feel hope and joy as well as a sense of sadness and loss. Susan Cain (the writer of Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World that Can’t Stop Talking and, more recently, Bittersweet: How Sorrow and Longing Make us Whole), in conversation with Simon Sinek, speaks about “the glimpses of transcendence that are always at hand” when we embrace the bittersweet in our lived experiences. Cain believes life is full of colour rather than black and white but that we are often “not allowed to talk about our sadness, pain and fear”. For Cain this is counterintuitive as she believes they are the “strongest gateway to creativity and people connecting with each other”. Cain describes the “sharing of sorrows as one of the great bonding mechanisms that humans have developed”. In the same conversation, Simon Sinek talks about how hard it is to “hold space” for others’ negative emotions, which are often more uncomfortable for the person listening than the person who is experiencing the emotion.

The use of the term negative by Sinek, though, is part of the problem. It is a subjective label – a value judgement – about the nature and quality of sadness, fear, anxiety or other emotions we would

typically describe as “negative”. By contrast, Cain revels in the concept of the “bittersweet” and suggests that people who allow the bitter and the sweet to sit side by side in their lives, and see both as of equal value, get into states of “wonder, awe and spirituality”. They embrace the complexity of life with a deep knowledge that what is painful and hard is temporary. Such people are also hopeful because they inherently believe in the capacity of human beings to navigate complexity successfully. Personally, I find Cain’s description beautiful because it describes what it means to be alive and to be human. The challenge at times of change and transition is to hold onto that sense of hope and to help our young people do the same when faced with the unknown of another school, another year, or life beyond HVGS.

Any point of transition contains both the bitter and sweet simultaneously. If I reflect on my own transitions between countries, each time, I have openly wept at leaving wonderful colleagues, students and parents and experienced great joy and excitement at the new possibilities on the horizon. Sometimes I have spoken about myself as being comfortable with change. Upon reflection I realise that I am not comfortable with change – nobody is, really – but because of my lived experience, I understand and am comfortable with the process of change. I know that it will take time and that it will be both bitter and sweet. I know that at times I will weep, and at other times I will experience a wonderful elation that is full of possibilities. Above all, I believe in my own and others’ ability to move through the bitter and the sweet as part of the change because, inherently, human beings are resilient. We bounce back.

However, the speed with which we bounce back, and the ease with which we embrace the bittersweet, is dependent on the stories we tell ourselves. If we see change as normal and know that at times it will feel good and at times really hard, we come to the process with a “not yet” mindset. If we know and understand that change involves emotional labour and is a process, then we know that we are only uncertain and in a state of chaos temporarily. We have “not yet” arrived at the skills, knowledge and understanding we need to embrace the change in all its entirety.

The late Bill Powell wrote a wonderful article that I have repeatedly returned to during a time of change or when supporting others with transition. The article is titled “Orchids in the bathroom” because, despite many prior international moves, Bill writes about the loss and anger he experienced moving from Indonesia to Tanzania. This loss was encapsulated by the absence of his much-loved orchids that hung in his Indonesian bathroom. The orchids became the signifier of the “bitter” aspect of his move; an example of all that he had lost as a result of his decision, as well as all that he felt was lacking about the school and country he had just moved to. Powell realised that he was fixating on the sadness of loss, which was ok, but to move through to embracing the change he needed to better understand change itself and reframe his thinking.

Powell’s article is powerful on two fronts: it normalises the emotional labour of change and talks about strategies for building the states of mind that help us tap into the “sweetness” of the move. Powell cites research on loss in younger children which identifies that:

If you think about this, your child will adjust to a new class, year, section of the school or school more quickly than you will as parents!

Knowing this information puts change into perspective. Powell knew that it couldn’t be rushed and that it would be hard for a while. In addition, Powell knew that one of the antidotes to the stress of change was taking charge of his state of mind:

“We have the power to influence our own state of mind and that of others. This revelation lies at the heart of effective teaching and learning. It can be as simple as offering a word or two of encouragement or as complex as psychotherapy. … Becoming consciously aware of one’s state of mind allows choice and change and ultimately allows us to take control of our lives.” (William Powell, “Orchids in the Bathroom”, International School Journal, 1st January 2001)

Drawing on the work of American Art Costa, Powell describes states of mind as transitory, transforming and ultimately transformable. As educators we know this, and it is part of the reason for our focus on Growth Mindsets. We know that the stories we tell ourselves, and the language we use, can be transformative or can keep us stuck.

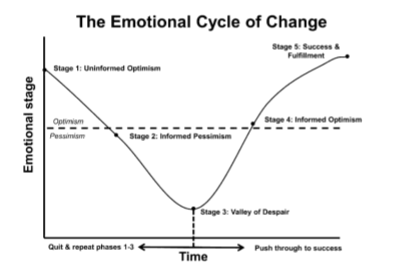

David Pollock and Ruth Van Reken have done significant work on Third Culture Kids and transition. They describe being in transit – going through a period of significant change – as a time of chaos and vulnerability because it is inherently messy. I have often used the diagram below when talking about change with staff:

We all know those moments of being in the “valley of despair”. These are the times when we know enough to understand that change will be uncomfortable and hard and that there will be no quick fixes. Being in this space can be overwhelming. However, the speed with which we come out of that pit of despair depends on our capacity to reframe the story we tell ourselves so that we can transform our habits of mind. As mentioned above, it is the power of “not yet” as opposed to “never”. For example, it is saying to ourselves “I don’t know what Senior School will be like yet” as opposed to saying to ourselves “I will never survive senior school!”. Or “I will never understand this new parent app” versus saying to ourselves “I don’t yet understand how to use this new app, but with practice I will.”

By working through change in this way we can become comfortable with the change process. We may never be comfortable with change itself – by its nature it is inherently uncomfortable – but by tapping into our own internal resources, normalising the change process and understanding a bit more about the psychology of change, we can hold space for the bittersweet and embrace the possibilities that change brings. For me this powerful because we it comes with it the knowledge that we have the resources within ourselves to choose to truly make change transformative.