Published on February 9, 2024

During our January Professional Learning Days, our Director of Teaching and Learning (Kelly-Ann Sackey) and I led our middle-level leaders through a workshop on systems thinking.

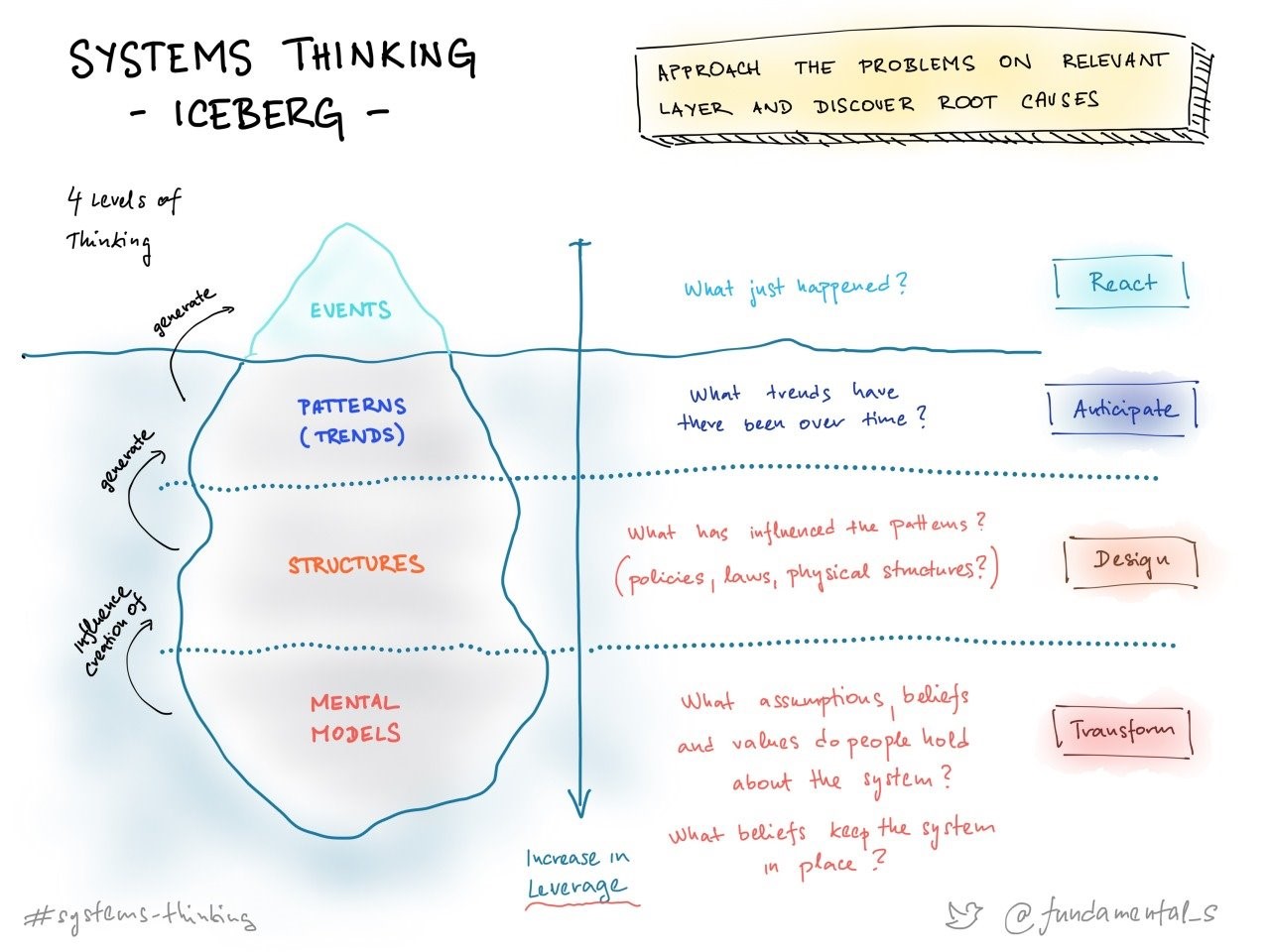

We often talk about systems thinking loosely, and assume we know what it is and how to do it. However, systems thinking is underpinned by a complex set of competencies and a rigorous process to get beyond surface-level thinking and problem-solving, to get to the heart of what is called a “wicked problem”.

Firstly, let me define wicked problems and I will use climate change as an example to illustrate each characteristic. A wicked problem has the following characteristics:

· Information related to the problem or components of it are contradictory or incomplete. The debates are climate change illustrate this complexity and the struggle to get global consensus on a way forward.

· There appears to be no end to the problem and to the timeline for fixing the problem. In the case of climate change, we have targets but they keep moving or being extended. It seems to be a problem with no clear end in sight.

· There are numerous stakeholders. In terms of the climate these stakeholders include future generations who are not yet born.

· Solutions are costly, and in the case of climate change, these costs are environmental, economic, social and cultural.

· Solutions are difficult to define and the problem is socially complex – we can see this with global and local debates around climate change!

· Issues are interconnected and solutions may cause new problems: for example, if we reduce carbon outputs, there is an impact on the mining industry, which has an impact on jobs and the local and national economy. Agricultural practices and livelihoods are impacted by flooding and fire; extreme weather events are increasing as our planet warms. Climate change involves a range of interconnected, complex issues, and solutions that impact people and groups in different ways.

· Solutions can’t be tested without implementing. When it comes to climate change, we have to try ideas to see if they are going to work, but the reality is it might take a significant period of time to be able to measure this impact.

I like to use Climate Change as an example of a wicked problem we are facing globally and nationally because it illustrates the following principle at the heart of systems thinking work:

“We’ve all heard the old saying that ‘if you’re not part of the solution, you’re part of the problem.’ But my systems thinking colleagues turn it on its head and say that ‘if you’re not part of the problem, you can’t be part of the solution.’ When you understand that you are part of the system, you understand that you are a part of the problem, and therefore, you can be part of the solution.”

Systems thinking is a powerful tool to get us, in Dan Heath’s words, “upstream” and out of the downstream reactive space in which we often find ourselves. To use a personal and very simple example, when I moved back to Australia in December 2021 I broke my exercise routine. As a result, I moved into a downstream space: I reacted to the absence of an exercise routine by getting annoyed with myself, doing brief stretches of intense exercise, being exhausted and then doing nothing, feeling bad and so the cycle continued. The cycle of reacting and being “downstream” was far from satisfying. Last year I paused, headed upstream in my thinking and worked to understand what was impeding my ability to be in a good routine. I needed people – others to hold me accountable for my exercise regime – so I made a change and have my routine back.

This is a simple example of the difference between being upstream versus downstream when we encounter a problem.

In schools, we can often feel like we are reacting, and our goal needs to be to pause, slow down, identify if there is a bigger system problem that we need to address, and then evaluate potential responses, actions and interventions in light of their impact on the system.

As we slow down and use more systems thinking tools at work and in our classrooms, we build the capacity to see our part within the system and thereby understand we have the power to make positive changes within the system. Building capacity means we are going deeper and closer to the root causes. Our goal should always be that our actions are getting us closer to the root causes and higher leverage change.

This takes time and we will still have to react sometimes. But, in the case of student behaviour, if we can understand the assumptions, beliefs and values that a young person has that are leading to problematic behaviour, then we have more chance of designing a solution with them that will address that behaviour and lead to long-term change. When I identified that the missing link in my exercise regime was external accountability, I was able to transform my mental model, and then put in place the structure I needed to get me moving again.

Here is another great description of systems thinking work:

All systems are perfectly designed to generate the behaviours they produce. This premise means that there is no one person or entity to blame when things aren’t going well. Instead of trying to figure out who is the cause or who is to blame, look at the way the system is designed and ask, ‘How is the system structured, and what is it about the current design that gets us to those disappointing results?’ and, ‘What role do I and do we play as design leaders of that system? Can we accept the possibility that the current system design is made to produce lacklustre results?

In 2024 we will talk a lot about systems thinking and how we build our capacity, and that of our students, to develop the Habits of System Thinkers. These habits are great tools to discuss at home and may help around the dinner table as you talk about the wicked problems the world, and our young people, are facing.

Systems thinking is not easy work, and most certainly not in schools. Schools are very complex, human-centred systems and most of us like “quick fixes”. What we need to remember is that there are no quick fixes that don’t have an unintended consequence within the system. It is the ripple effect: we need to truly understand what happens when we toss that pebble (that quick fix) into the pool and who/what will be impacted by the ripples that emerge. It doesn’t mean we don’t do a quick fix, but we need to do it understanding the implications it will have for the system and knowing that it stall the path to real transformation.

You can read more about systems thinking in the Education Changemaker’s Guide to Systems Thinking.